by Neil Watson

Although it certainly cannot be said that Futurism is unknown, I think it is true to say that it has not permeated the public consciousness to the same extent as other twentieth century art movements, possibly due to its brief period of existence. However, Constructivism and Abstraction in its various forms would not exist without Futurism; it is an essential stepping stone in the evolution of art and, in my opinion, Futurist artworks exhibit a purely aesthetic beauty that can be absent from those emanating out of successive movements.

I was fortunate enough to attend the major exhibition ‘Le Futurisme à Paris’, held at the still-controversial Centre Pompidou in Paris late last year. I was there for a trade fair connected to my work, but decided to couchsurf over the weekend with the delightful Ganit, an Israeli lady living not far from the Père Lachaise Cemetery. She knew of my interest in art, so we discussed the various exhibitions taking place and decided that this would be particularly good. She also invited her Algerian-born friend Yasmine, who works for a government agency and was thus able to invite me, free of charge, to the exhibition. It was great to view the exhibition with two genuinely interested people with long attention spans who wanted to absorb the 200 exhibits and periodically discuss their reactions.

Even the design of the exhibition was designed to evoke the spirit of the cityscapes painted by the Futurists. The central space amongst the rooms represented a town square; just off this was a red-walled room housing a reconstruction of the Italian Futurist exhibition held at Bernheim-Jeune & Cie in 1912, whilst the adjacent streets each led to rooms dedicated to Cubo-Futurist movements.

Rejecting the past

The major impetus behind the exhibition was the forthcoming centenary of the movement, which evolved amongst a group of Italian artists, dramatists, philosophers and poets living in Paris. The movement was formally launched on the front page of Le Figaro, dated 20 February 1909, with the publication of the Futurist Manifesto, written by the poet and dramatist Filippo Marinetti (1876–1944). Marinetti’s manifesto was inflammatory, and is regarded as representing the birth of the avant-garde. He stated: ”Art [...] can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice. […] We want no part of it, the past. We will fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless and snobbish religion of the past, a religion encouraged by the vicious existence of museums. We rebel against that spineless worshipping of old canvases, old statues and old bric-a-brac, against everything which is filthy and worm-ridden and corroded by time. We consider the habitual contempt for everything which is young, new and burning with life to be unjust, and even criminal.”

The Futurists admired machinery, speed, movement and crowds, representing the technological triumph of humanity over nature. They were also staunchly nationalistic; even Fascist – Marinetti later became a staunch supporter of Mussolini. The first room of the exhibition dealt with the reaction against the prevailing Cubist movement. In particular, they rebelled against the prevalence of the nude in Cubist art, which harked back to traditional art and counteracted the expression of modernity. The 1910 Manifesto for Futurist Painters stated: ”We recommend, for ten years, the total suppression of the nude in painting!”

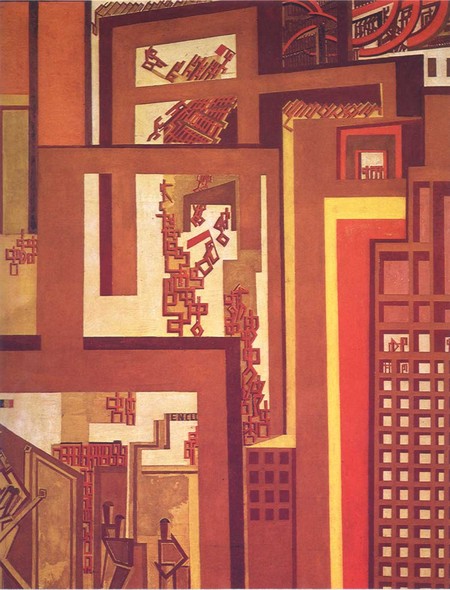

The Crowd by Percy Wyndham-Lewis

Speed and vitality

The recreation of the first Futurist exhibition, held at the Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris in 1912 was particularly interesting. This exhibition encompassed the works of the main artists in the movement – Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Gino Severini and Giacomo Balla, demonstrating the application of the theories expressed in the 1910 Manifesto. The paintings evoked the movement and energy of modern cities – particular themes were railway stations and geometrical architectures framing man and machine. Some of the most famous examples were Boccioni's The City Rises, which juxtaposes scenes of construction alongside a rearing red horse in the centre foreground, which workmen struggle to control. Another was Balla's Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, demonstrating that the perceived world is in constant movement. The painting depicts a dog whose legs, tail and lead, together with the feet of the owner, have been multiplied to a blur of movement. The three main principles were taken from philosopher Henri Bergson – ”Dynamism”, ”Duration” and ”Simultaneity”. After Paris, the exhibition travelled to London and Brussels.

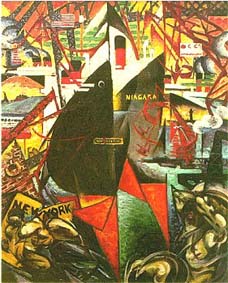

Despite its evolution in France, only one French painter sympathised with the Futurist cause – Félix Del Marle. He began an acquaintance with Gino Severini in 1906 and wrote his Futurist Manifesto against Montmartre. Published in Paris-Journal in 1913, this directed commented on the deification of Montmartre in the wake of the Impressionists and Cubists: ”Your Moulin de la Galette will be swallowed up by a Metro station. Your flea-ridden Place du Tertre will be crossed by buses and trams, and from all the dung that you are trying to defend today, an apotheosis of skyscrapers will rise to pierce the heavens, great blocks of houses infinitely tall.” His most famous painting from this period was The Port, which simultaneously shows several perspectives of a ship, its cargo and the port infrastructure.

The Port by Félix Del Marle

Unhappy cohabitation

Despite the disdain for Cubism, there was some artistic dialogue between the Futurists and Cubists. Following the publication of the Futurist manifestos in the French press, the Bernheim-Jeune exhibition and the exhibitions of Cubist works in Paris, a certain amount of hybridisation took place. After 1912 certain Cubists, including Juan Gris and Robert Delaunay, brightened their pallets and tried to escape the sombre colours simulating collages. A prime example is City of Paris by Delaunay, which depicts the Three Graces in front of the cityscape, which includes the Eiffel Tower. On the other hand, the Futurists Boccioni and Severini began to produce still-life paintings, employing greys and ochres.

City of Paris by Robert Delaunay

In October 1912, some Cubist painters organised the Salon de la Section d’Or exhibition as a response to the Bernheim-Jeune exhibition, its name referring to the ‘golden section’ or ‘divine proportion’, evoking geometrical concepts. When viewing the exhibition, Guillaume Apollinaire spoke of a ‘divergent Cubism’, where there was synthesis between Cubism and Futurism. The most well-known artwork to emanate from this period was Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, which he described as a ”Cubist interpretation of a Futurist formula.” This is regarded as the inception of the Cubo-Futurist movement.

Introducing the new Futurism, and particularly Cubo-Futurism, was well-received in Russia. The Futurist Manifesto was published in a Russian newspaper a month after its publication in Paris. Its initial influence was purely literary, but the first Russian artist to apply Futurist concepts was David Burliuk, who wrote the Russian Futurist manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. His works emphasised vitality in various forms, most notably in Revolution (1917). He was joined by Khlebnikov, Kruchenykh, Mayakovsky and Matiushin in what was dubbed the Cubo-Futurist Group. That year, Kazimir Malevich theorised Cubo-Futurism, which Marinetti considered to have outstripped his own Cubist philosophy. This culminated in Suprematism, an art movement focused on fundamental geometric forms, such as the square and circle. This embodied the vitality and simultaneity of Futurism, but reacted against form.

In April 1910 Marinetti visited London to deliver his Futurist Speech to the English. He found many young artists who had visited London and become aware of the Futurist aesthetic. Percy Wyndham-Lewis helped establish the journal Blast, which attracted a group of artists who focused on Cubo-Futurism, particularly concentrating on architecture and machinery, combined with Cubist formalism. A prime example was The Crowd (1915), where human beings are dwarfed by a skyscraper. The poet Ezra Pound used the word ‘vortex’ to describe the style of this work, and it subsequently became known as ‘Vorticism’.

The final direction of Futurism was Orphism, the name being coined by Apollinaire in a talk to the Section d’Or in 1912. This was a synthesis of the ‘pure’ painting associated with Cubism with the ‘simultaneity’ that was favoured by the Futurists. This led to accusations of plagiarism by the Futurist Umberto Boccioni, but in fact revealed the relationship between Futurist and Cubist values, epitomised by Sonia Delaunay in Prismes Électriques (1914), geometrically depicting the colours simultaneously emanating from three electric light-bulbs in street-lamps.

Prismes Électriques by Sonia Delaunay

This was a wonderful exhibition. I loved the colours, modernity and vitality of Futurism and the organisation of the exhibition demonstrated how it impacted the future direction of art in various ways.

- Neil Watson, a regular contributor to Turntable & Blue Light.